In the short book of Philippians—only four chapters long—

Paul uses the word joy sixteen times.

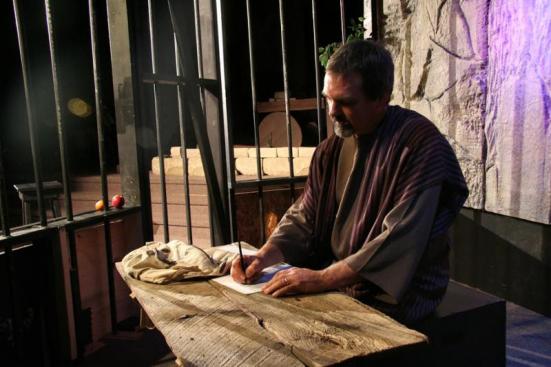

Paul didn’t write this book during spring break. He wrote it from a prison cell in Rome while he was waiting to be executed. In what should have been the darkest days of his life, he wrote the most encouraging book in the Bible.

Paul did not write from a position of denial but from a position of sober and joyful reality. Right there in his chains, he wrote about “the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord, for whose sake I have lost all things” (Phil. 3:8).

Paul knew something; he experienced something. The word he uses here to describe his experience—his knowing—isn’t theoretical. It’s not knowing like you might know about the ancient Sumerians or the law of thermodynamics. The word is gnosis, a deep, personal, intimate knowledge. Paul had experienced God in such a way that even in jail he could find a very real joy as he fixed his gaze on Jesus.

He wasn’t faking it either; he wasn’t living in some form of spiritualized denial. Here in his treatise on joy he speaks honestly of his sufferings (Phil. 1:29–30). He later describes being “poured out like a drink offering” (2 Tim. 4:6). Paul wrote his letters with an indisputable hope that burned all the brighter because he didn’t deny his suffering.

Whatever else this means, it tells us that joy is available no matter our circumstance. Good heavens—Jesus went to the cross with a view of joy before Him (Heb. 12:2). As the psalmist wrote, “Weeping may stay for the night, but rejoicing comes in the morning” (Ps. 30:5).

This isn’t the Christian bait-and-switch. This isn’t for “someday.” No. Joy is promised now, and it is our inheritance. There is a way to joy. The key is walking that way with our gaze set on Jesus, even when the way is dotted with suffering.